1. Two-Minute Recap

In “Introduction to Functional Decision Theory”, I described Yudkowsky & Soares’ Functional Decision Theory (FDT) as an alternative to Causal Decision Theory (CDT).1 When facing a dilemma, CDT asks “Which action would cause the best outcome?” and FDT asks “Which action would yield the best outcome if FDT recommended it?” These two questions diverge in their answers when it comes to certain predictive dilemmas: problems in which your opponent makes a move that is predictive of what you will do, by some sort of “subjunctive dependence” (more on this later).

For instance, suppose you are cloned and then face a prisoners’ dilemma against your twin. CDT will reason that what you choose now has no causal impact on what your twin chooses (provided you are isolated in separate rooms and cannot communicate). If they defect, you do better by defecting too; if they cooperate, you still do better by ripping them off and defecting. You and your twin both predictably reason this way, and you get mutual defection, which is worse for both of you than mutual cooperation.

But FDT reasons: you and your twin are deterministic copies. If you follow FDT, so does your twin, so you will both do whatever FDT endorses. If FDT endorsed defection in twin prisoners’ dilemmas (henceforth twin PDs), then the outcome would be mutual defection. If FDT endorsed cooperation in twin PDs, then the outcome would be mutual cooperation. It would be better for you if FDT endorsed cooperation; therefore, FDT does endorse cooperation.

A key argument for FDT over CDT is that CDT does not endorse itself in dilemmas like these: if a CDT agent had the option to reprogram itself to cooperate in future twin PDs, such an action would cause it to have better outcomes in those twin PDs, so a CDT agent would program itself to not be a CDT agent in twin PDs, while FDT does no such thing.

Unfortunately for Yudkowsky & Soares, there is a very simple class of problems for which their formulation of FDT doesn’t endorse itself either—and these problems, we shall see, undermine their entire justification for FDT as a theory.

2. Hypothetical Reasoning

To understand how FDT fails, we need some formal structure. According to Yudkowsky & Soares, CDT and FDT are both “expected utility theories,”

meaning that they prescribe maximizing expected utility, which we can define (drawing from Gibbard and Harper [1978]) as executing an action a that maximizes

All this equation says is that the expected utility of an action a is just a weighted sum: multiply the utility of each possible outcome (oj) by the probability of that outcome obtaining given your information about the scenario (x) and that you choose action a (a ↪ oj ), then add it all up. Then we take the action that has this highest expected utility value. Where different decision theories diverge is in how to handle a ↪ oj given x. To calculate the probability that a will lead to oj, we need to model a hypothetical: “what would happen if I took this action, given these observations, all else held equal?”

CDT constructs causal hypotheticals. Since you and your twin are now separate and unable to communicate, your choice does not cause theirs, CDT imagines hypotheticals where your action is different but your twin’s action is held equal. CDT’s hypotheticals ask, “what would causally change if I took this action given this observation history?”

FDT constructs what Yudkowsky & Soares call subjunctive hypotheticals. You and your twin both follow the same decision theory, so your choices “subjunctively depend” on what FDT recommends.3 FDT imagines hypotheticals where FDT’s endorsement changes, which modifies both you and your twin’s action. FDT’s hypotheticals asks, “what would be the consequences if FDT recommended this action given this observation history?”

It’s important to note that this is as far as FDT’s recursive-style reasoning goes. FDT only reasons about what would be the best output for FDT to recommend, not about what its axioms should be or how it should construct and evaluate hypotheticals. This level of strictness prevents it from being too circular. But, as we’ll see, its limitation to considering only this kind of hypothetical may be part of its downfall.

3. An Asymmetric Twin Problem

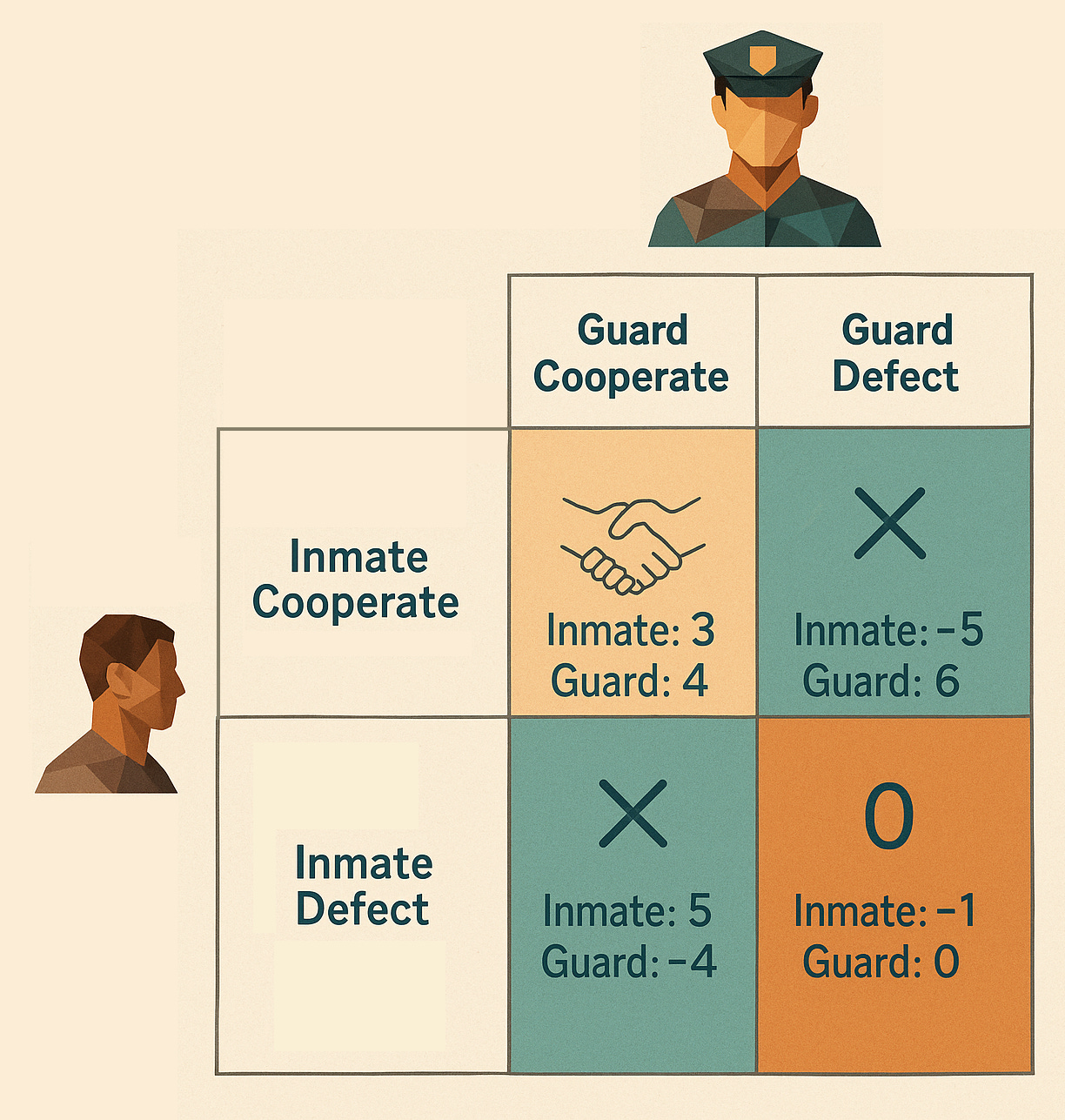

Imagine a slight variation on a prisoners’ dilemma, where one player is randomly assigned the role of the “guard”, the other the “inmate.” Let’s call this the guard-inmate dilemma, or GID for short. The payoffs are exactly identical to a classic prisoner’s dilemma, but in all cases, the guard gets +1 extra utility:

CDT reasons that whether or not you’re a guard or an inmate, no matter what action your opponent takes, defection always serves you best. If your opponent is not a twin and does not follow FDT, FDT agrees, since there is no subjunctive dependence between you.

Now suppose you are competing against your clone, in a twin GID, and you learn you are the inmate. CDT’s reasoning stays exactly the same and endorses defection. But FDT’s recommendation is suddenly more difficult. Recall that in the expected value formula,

the probability calculation is dependent on your observation history x. In a normal twin PD you and your twin have identical observation histories, so when you are imagining what would happen if FDT recommended cooperation on your observation history, that recommendation also applies to what someone should do given your twin’s observation history—you are choosing for both of you. It’s impossible for f(x) = COOPERATE for one person and f(x) = DEFECT for one person given the exact same f and x. Hence the subjunctive dependence in a normal twin PD.

But now your observation history includes your “inmate” status, whereas your twin’s observation history now includes their “guard” status. You are no longer computing with respect to the same input: f(x∪ {“guard”}) is not necessarily equal to f(x∪ {“inmate”}) for every possible function f. So do your decisions subjunctively depend on one another, or not?

If they don’t, then you are back in the normal GID, where what FDT decides for your particular observation history doesn’t affect the other person’s action. Then FDT, like CDT, recommends defection.

If they do, how are they related? I see two ways: either you and your opponent must take the same action, or you must choose some sort of rule for how to behave in twin GIDs, which both you and your twin would follow.

If you must take the same action, this works fine for twin GID and you can cooperate. But if this is how subjunctive dependence works, FDT can’t address coordination problems in which you and your twin need to do different things. For instance, suppose immediately after the twin GID there are two lifeboats, labeled G and I, each with room for only one passenger, and you and your twin have to independently decide which one to run to before the boat sinks, each losing 10 utility if you arrive at the same boat. A strategy that stipulates “the guard should run to lifeboat G, the inmate should run to lifeboat I” outperforms a strategy where you both have to pick the same lifeboat to run to. But if subjunctive dependence means that guard & inmate have to make the same choice, they cannot execute on this. What makes the subjunctive relationship in the lifeboat scenario different from the GID?4

If you are permitted to take different actions, the dependence must rest on choosing a common rule that both of you must follow, like the letter-room rule from the lifeboat scenario. In that case, your reasoning, per the expected-utility formula, would go “what rule would, if FDT recommended that rule in twin GIDs, lead to the best outcome for me, given my observation history?” Since you are the inmate, and your twin is the guard, the best rule for you would be “cooperate if you are a guard, defect if you are an inmate,” which would yield an expected utility of 5 for you. (The rule “cooperate whether you are a guard or an inmate,” by contrast, would only yield an expected utility of 3 for you.) Since it would be best for you if FDT recommended that rule, FDT by definition recommends that rule, and so therefore you, being an inmate, should defect. The problem is that your twin will reason in a mathematically distinct yet parallel way! Given that your twin is a guard, the best rule for your twin would be “defect if you are a guard, cooperate if you are an inmate,” and therefore your twin reasons they should defect. So both of you will defect.

In sum, all interpretations of what “subjunctive dependence” means lead to either mutual defection in a twin guard-inmate dilemma, or an FDT which can’t handle asymmetric coordination in a twin lifeboat dilemma. If you are an inmate, it would be best for you if FDT recommended that inmates should defect and guards should cooperate; if you are a guard, it would be best for you if FDT recommended that guards should defect and inmates should cooperate.

Of course, we can see that reasoning this way will lead to a situation where you and your twin will both defect. But FDT isn’t equipped to realize this. Remember that FDT evaluates an action a under observation history x by considering hypothetical cases in which FDT endorses a for all agents with observation history x. In those hypothetical cases, either your twin’s action is independent of yours (so you should defect) or you are setting a policy for both of them, and in the hypothetical where both follow the policy “defect if inmate, cooperate if guard” is best for you. The only way to avoid defection is to somehow make this hypothetical “illegal” by claiming it violates subjunctive dependence. But it’s difficult to see how. The rule “defect if inmate, cooperate if guard” does not logically contradict itself. It’s well-defined as a piecewise function. Sure, it’s kind of a weird commitment, but then so is one-boxing in Newcomb’s problem. It looks like FDT is stuck with mutual defection in a twin GID.

Which brings us to the killshot: agents which always cooperate in a twin GID and take asymmetric action in a twin lifeboat scenario outperform FDT agents in expected value.

3. Why This Damns (Y&S’s version of) FDT

If you haven’t read Eliezer Yudkowsky’s personal beliefs on rationality, you might not immediately realize how damning this is for FDT as his pet theory. FDT’s entire justification for existence was that agents who would one-box in Newcomb’s problem or cooperate in a twin PD perform better than those who don’t. Here’s that quote from Yudkowsky on what rationality means in my FDT 101 article:

Rational agents should WIN … at any rate, WIN. Don’t lose reasonably, WIN. Rather than starting with a concept of what is the reasonable decision, and then asking whether "reasonable" agents leave with a lot of money, start by looking at the agents who leave with a lot of money, develop a theory of which agents tend to leave with the most money, and from this theory, try to figure out what is "reasonable". "Reasonable" may just refer to decisions in conformance with our current ritual of cognition - what else would determine whether something seems "reasonable" or not? … You shouldn't claim to be more rational than someone and simultaneously envy them their choice - only their choice. Just do the act you envy.5

If FDT doesn’t win, that’s the ballgame for Yudkowsky. Other decision theorists might throw up their hands and say that twin GID is just a problem that rewards being irrational, but not Yudkowsky. He makes it very explicit when he considers a problem perversely punishing and when he considers it a fair test. Here he is on Newcomb’s problem (where “Omega” is the name of the predictor):

I can conceive of a superbeing who rewards only people born with a particular gene, regardless of their choices. I can conceive of a superbeing who rewards people whose brains inscribe the particular algorithm of "Describe your options in English and choose the last option when ordered alphabetically," but who does not reward anyone who chooses the same option for a different reason. But Omega rewards people who choose to take only box B, regardless of which algorithm they use to arrive at this decision, and this is why I don't buy the charge that Omega is rewarding the irrational. Omega doesn't care whether or not you follow some particular ritual of cognition; Omega only cares about your predicted decision.6

Twin GID is not one of those problems where a superbeing Thanos-snaps everyone who believes in FDT out of existence. Twin GID only cares about your actions. So according to Yudkowsky’s view of what constitutes a fair problem (which I agree with), this is all on FDT.

This also means, as we mentioned in the beginning, that FDT doesn’t endorse itself in twin GIDs. If given an opportunity in advance to pre-commit to cooperation regardless of guard/inmate role, FDT would take it. To be clear, so would CDT; I have yet to find a fair problem in which FDT doesn’t endorse itself but CDT does. But CDT has a lot of other advantages: it makes more intuitive sense, it doesn’t have counterpossible reasoning looming over its head, there are developed ways to determine causal structure (who the hell knows how to model subjunctive dependence, because Yudkowsky & Soares don’t). FDT’s practical edge and self-endorsement are about the only things going for it, and it loses both of them in twin GID, and probably many other asymmetric games as well.

4. Alternatives

There is hope for a decision theory that can beat FDT and CDT. After all, I was able to figure out that you should endorse cooperation in a twin GID, even thought FDT disagrees with me. I feel pretty committed to that decision, committed enough that I’m confident if I was put in a twin GID, I would achieve a mutual cooperation outcome. I hope you readers feel the same way now. If we can outperform FDT here, so could another theory! Some options:

I got to this conclusion by reasoning not just about what actions FDT recommends, but about how FDT reasons—what the rules are for constructing and evaluating hypotheticals. Perhaps one could develop some meta-FDT, which reasons about what hypothetical-reasoning process would lead to the best state of affairs. Maybe it wouldn’t involve hypotheticals directly at all, but would produce a set of axioms which it would be best if all FDT agents behaved according to. Hard to formalize, though—one advantage of the subjunctive-dependence-graph approach was that it let you tackle isolated outputs of FDT in individual problems, rather than overhauling the entire system for each new problem, and a lot of work will be needed to ensure non-circularity.

Before publishing this article, I asked Claude to steelman FDT and look for flaws in my argument (something I recommend more writers do!). Claude suggested that FDT use ex-ante or “veil of ignorance” reasoning, determining which policy of action you would want FDT to recommend if you didn’t know what role you were going to be placed in. This would work for both twin GID and twin-lifeboat problems. However, I suspect ex-ante approaches will have a hard time determining what information should be treated ex-ante and what should be treated ex-post; I need to do some reading on updateless decision theory.

I asked Claude for 10 more proposals on how to fix this. None of the original ones looked particularly good to me, but one possibility it suggested would be to consider what conclusion agents would arrive at if they were able to communicate and negotiate. This makes me wonder if we could establish pricing for what agents would pay to have other agents act differently, and take whatever equilibrium an efficient market would converge on. Pretty speculative, but worth a look.

If you have ideas or suggestions, please leave a comment below!

Yudkowsky, Eliezer, and Nate Soares. “Functional Decision Theory: A New Theory of Instrumental Rationality.” arXiv, May 22, 2018. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1710.05060.

Yudkowsky & Soares 11. They are referencing Gibbard, Allan, and William L. Harper. 1978. “Counterfactuals and Two Kinds of Expected Utility: Theoretical Foundations.” In Foundations and Applications of Decision Theory, edited by Clifford Alan Hooker, James J. Leach, and Edward F. McClennen, vol. 1. The Western Ontario Series in Philosophy of Science 13. Boston: D. Reidel.

Yudkowsky & Soares 6.

In other words, subjunctive dependence shouldn’t inhibit your ability to use Schelling points.

Emphasis in original. Yudkowsky, Eliezer. “Newcomb’s Problem and Regret of Rationality,” January 31, 2008. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/6ddcsdA2c2XpNpE5x/newcomb-s-problem-and-regret-of-rationality.

Ibid.