1. One-Minute Intro

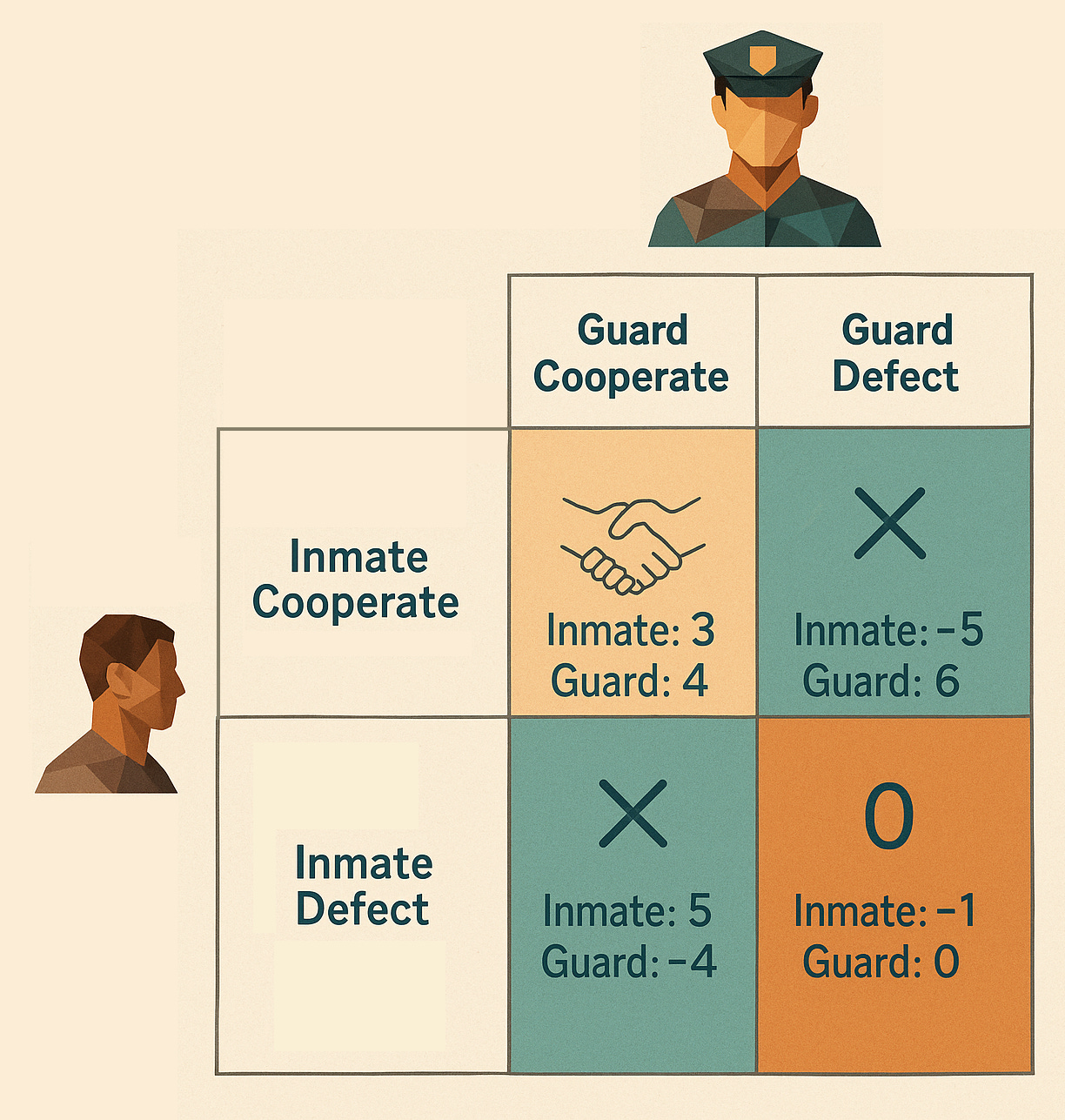

The guard-inmate dilemma (GID) is just like the prisoner’s dilemma, except that the guard’s payoff for every outcome is 1 utility point greater. A twin GID is when you are made to play a guard-inmate dilemma against an exact copy of yourself, and after the copy is made, who gets to be the guard and who gets to be the inmate is randomized. Here’s the payoff matrix:

As I wrote in my last post, twin GIDs destroy Functional Decision Theory:

To summarize:

If you learn that you are a guard, it would be best for you if FDT recommended “guards defect, inmates cooperate.”

If you learn that you are an inmate, it would be best for you if FDT recommended “inmates defect, guards cooperate.”

Therefore, if you and your twin both follow FDT, you will both defect.

An alternative decision theory that says “just cooperate in a twin GID no matter your role” would outperform FDT, since both you and your twin would follow it and therefore mutually cooperate.

If you know you are going to be in a twin GID, it would be better for you if FDT recommended converting to this alternative decision theory ahead of time.

Therefore, FDT recommends converting to a decision theory other than FDT…

…which undermines Yudkowksy & Soares’ entire motivation for FDT. It was supposed to be the decision theory which endorses itself, the decision theory where agents who follow it empirically outperform the alternatives. Neither claim is true.

However, that doesn’t mean it can’t be done. Fixing FDT’s problems will take time and work, but I hope to emerge with either a new decision theory, a ringing endorsement of an existing one, or an impossibility theorem. Today, I’ll highlight what I think will be a key element of the solution: obeying ideal forethought, rather than ideal hindsight.

2. Lotteries and the Twin GID

On Monday, Ben has the chance to buy lottery ticket #351 for $1 in a lottery that will pay out $1,000,000 to the singular winning ticket, which has been determined in advance. Ben makes his decision by calculating expected value. There are ten million tickets, so the expected value of buying the ticket is -$1 + $106 × 10-7 = -$0.9. The expected value of not buying the ticket is $0. $0 > -$0.9, so he doesn't buy. On Tuesday, the winner is announced, and what do you know—lottery ticket #312 was the winning ticket.

"Darn!" thinks Ben. "I wish I had followed a decision theory that recommended buying ticket #312."

Seems like a weird wish, but let's humor Ben for a moment. Let Ben's decision theory be a function B such that B(x, U) := the *action* Ben should take in scenario x which maximizes the expected value of his utility function U. Let B* be a different decision theory, defined:

If Ben followed B*, he would have made $999,999. If Ben followed B, he would have made $0. ∴ It would have been better for Ben if he had followed B*.

Does that mean B* is a better decision theory than B? No! From Ben’s epistemic vantage point on Monday, ticket #312 was extremely likely to be a loser. Given the information Ben had at the time, Ben made the choice that maximized his expected value. Here is the distinction:

B* is superior to B in hindsight. That is, if you calculate the expected value of following B* vs. following B on Monday given the information Ben gains on Tuesday, then EV(B*) > EV(B).

B is superior to B* in forethought. If you calculate the expected value of following B* vs. following B on Monday given the information Ben had at the time, then EV(B) > EV(B*).

It sounds trivial, but failing to make this distinction is exactly why FDT doesn’t endorse itself in a twin GID!

If you discover you are an inmate, then the optimal policy for you to have precommitted to in hindsight is “inmates defect, guards cooperate”; vice versa if you discover you are a guard. If you follow hindsight reasoning, you and your twin will come up with incompatible, self-serving strategies and end up with mutual defection.

If you find yourself in a twin GID, there are four strategies you could have precommitted to in forethought, the moment before you were cloned: always cooperate, always defect, inmate defect & guard cooperate, or inmate cooperate & guard defect. In forethought, you wouldn’t know which role you were going to play, so you’d assign a 50% chance to ending up guard, 50% to ending up inmate. If you run the expected value calculation given those probabilities, the “always cooperate” policy is the best policy you could have precommitted to. You and your twin will both follow this policy, and therefore you will end up with mutual cooperation.

Forethought reasoning beats hindsight reasoning in a twin GID. FDT employs hindsight reasoning. Therefore, if you’re going to face a twin GID, it’s better to switch to a decision theory that employs forethought reasoning (on twin GIDs, at least).1

3. Forethought Precommitments

Yudkowsky & Soares should’ve been more careful about saying things like like “FDT agents simply act as they would have ideally precommitted to act. Another way of articulating this intuition is that we would expect the correct decision theory to endorse its own use.”2 As we’ve just seen, these are in fact two separate and sometimes contrary principles! …so long as the “ideal” precommitment is determined by hindsight. What about a theory that operates on foresight reasoning instead? After all, I think Yudkowksy & Soares’ argument from precommitment is pretty strong:

Argument from precommitment: CDT and EDT agents would both precommit to one-boxing if given advance notice that they were going to face a transparent Newcomb problem. If it is rational to precommit to something, then it should also be rational to predictably behave as though one has precommitted. For practical purposes, it is the action itself that matters, and an agent that predictably acts as she would have precommitted to act tends to get rich. … we note that precommitment requires foresight and planning, and can require the expenditure of resources—relying on ad-hoc precommitments to increase one’s expected utility is inelegant, expensive, and impractical.3

What Yudkowsky & Soares are actually describing is forethought reasoning! The CDT and EDT agents would precommit to one-boxing in advance, therefore one-boxing is rational. We can see that forethought reasoning aligns with other FDT recommendations, too:

Parfit’s Hitchhiker: in the desert, right before the driver reads your mind, you would’ve wanted to precommit to ensure you actually pay up when you get to the city. You should follow whatever policy would’ve been ideal to precommit to in forethought. Therefore, you should actually pay up.

Blackmail: before the blackmailer makes their prediction about whether you’re receptive to blackmail, you would’ve wanted to precommit to never caving to blackmail. Therefore, you shouldn’t cave.

Death in Damascus: if you had precommitted to fleeing Damascus before Death predicts where you’ll be, Death will predict you’ll be in Aleppo; if you precommitted to staying put, Death will predict you’ll be in Damascus. Forethought reasoning says either way Death will get you, so you should’ve at least precommit to the one that gives you the least travel costs (staying put).

In short, doing what the ideal forethought-reasoning precommitment would have recommended seems like a viable strategy, if it can be formalized.

4. Flexible Forethought Reasoning

One apparent problem with forethought reasoning might be scenarios like this:

Inverted twin PD. You are told that you are about to be cloned and enter a twin prisoners’ dilemma. Naturally, you know the smart policy to precommit to is mutual cooperation. But, oh no! After you are cloned, you and your twin are told that in this game, the payoffs are reversed! Now mutual defection is the best global outcome, and mutual cooperation is the Nash equilibrium. What do you do?

At first, it might seem like forethought reasoning is stuck. Before you were cloned, you didn’t know that the payoffs were going to be reversed, so you wouldn’t have precommitted to defection.

But this changes if you consider, not what actions you would have ideally precommitted to, but what policies, where a policy is a rule that stipulates what you should do if you learn certain information. So you, in the past, could very well have reasoned “I will precommit to the following. if this turns out to be a trap and the payoffs are reversed, then I must defect. Otherwise, I must cooperate.”

This might seem suspiciously close to hindsight reasoning, but it’s not. A forethought reasoner who thinks in terms of these if-then policies still wouldn’t embrace the rule “if I turn out to be an inmate, then I should defect,” since your past self still wouldn’t know if you’re going to end up an inmate. Hindsight reasoners who are inmates, in contrast, would love that policy, since they are holding constant the fact that they are an inmate. Thus, foresight reasoning can still handle these problems as long as it describes a policy of what you should do given a particular observation that you might or might not have.

5. Is This Just UDT?

Updateless Decision Theory is an alternative decision theory built along similar principles to FDT, while FDT was still in incubation at MIRI. Looking at its description:

UDT specifies that the optimal agent is the one with the best policy—the best mapping from observations to actions—as estimated by its prior beliefs. ("Best" here, as in other decision theories, means one that maximizes expected utility.)4

It sure sounds like forethought reasoning to me!

Not having looked that closely at UDT ahead of time, I had assumed that UDT and FDT were more or less the same in the recommendations that they made, and only diverged in their algorithms for arriving at those recommendations. And FDT seemed so much cooler with that sexy recursive reasoning… But after writing this piece, it seems to me that, depending on how UDT is formalized, they might really be fundamentally different!

(this, kids, is why you should do a thorough literature review before you write stuff on the internet!)

I’ll be carefully reviewing UDT before my next decision theory post, to catch if (a) UDT actually does diverge from forethought, (b) forethought is also a flawed form of reasoning, (c) UDT is awesome in theory but hard to model efficiently, or (d) UDT is awesome on all counts and I will defend it to the death.

My bet is on (b) or (c), especially given cheery recent LessWrong posts like this one: “Updatelessness doesn't solve most problems.” Plus, I have a couple ideas on how preference changes & certain types of wireheading might break even a very flexible forethought decision theory. If I find (d) to be the case, I will happily debate anyone who wants to take the opposing view. More investigation needed, but whatever I find, I’ll write about here!

“But wait! Isn’t FDT supposed to recognize this and tell you to follow whatever decision procedure leads to the best outcome?” Nope. Look carefully at the FDT equations; they tell you you should select whatever action would lead to the best outcome if FDT recommended taking that action on your current world model and observation history. Your observation history includes your role in the game (it has to, or FDT fails at basic asymmetric coordination problems), so either (a) you and your twin’s actions are totally decoupled, in which case it’s treated like a regular PD, or (b) you select your action based on an EV calculation over hypotheticals that use hindsight reasoning. In the moment, FDT insists defection is the right thing to do. More details in my last post.

Yudkowsky, Eliezer, and Nate Soares. “Functional Decision Theory: A New Theory of Instrumental Rationality.” arXiv, May 22, 2018. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1710.05060. Page 9-10.

Yudkowsky & Soares 9.

Demski et al. “Updateless Decision Theory.” LessWrong, January 10, 2025. https://www.lesswrong.com/w/updateless-decision-theory.